orco.pages

Advanced usage

In this guide we show additional functionality offered by ORCO.

Attaching data

Attaching basics

Job may have attached arbitrary data called “blobs”. Therefore a job may have more results than just a single result returned by the builder function.

Each blob has a name, MIME type, and content (raw bytes). ORCO provides helping methods for directly storing Python objects, text and some others.

Blobs are attached to a currently running job via orco.attach_ functions.

Calling these functions outside of job throws an exception.

import orco

@orco.builder()

def my_builder(x):

# Attach any picklable object

orco.attach_object("my_object", x + 2)

# Attach object as text, mime type is set as text/plain

orco.attach_text("my_text", "This is a text")

# Attach raw binary data

orco.attach_blob("my_data", b"raw data")

# Attach raw binary data, set mime type

orco.attach_blob("my_data2", b"raw data", mime="application/my-app")

When a job is finished data can be accessed via following method:

job = orco.compute(my_builder(10))

# Retreive blob and deserialize it by pickle

obj = job.get_object("my_object")

# Retraive blob and decode it as UTF-8 string

text = job.get_text("my_text")

# Retraive blob as it is; a pair (bytes, mime_type) is returned

data, mime = job.get_blob("my_data")

Blob is attached immediately as the attach_* method is called and it stays

there even the computation is not successfully finished. Hence it may be used

also for storing debugging information for failing jobs. Also already attached

blobs of running jobs is observable in ORCO Browser.

File-system helpers

There are also helping methods for interaction with file system: attach_file

attach a content of a file and attach_directory packs directory into a tar

file and attach it as a blob.

There are also jobs’ methods for working with filesystem: .get_blob_as_file

that stores a blob contant into a file and .extract_tar that extracts a

given blob as tar file.

@orco.builder()

def my_builder(x):

# Create a blob from a file

orco.attach_file("myfile.txt", x + 2)

# Create a blob from directory packed as a tar

orco.attach_directory("path/to/a/directory")

Blob names

The user may used any non-empty string that does not start with “!”. Default value, error messages and some other data attached to a job is stored also as a blob. They use a special names and never clashes with the user names.

- None (the only non-string name allowed) is the name of the default value.

- “!message” is error message when jobs fails

- “!output” is the standard output (see Capturing output)

Caching

Job’s methods returning blobs never cache the resulting value. This means that every time you retreive an attached blob, it is always freshly loaded from the database.

result1 = job.get_object("my_object")

result2 = job.get_object("my_object")

result1 and result2 should be equivalent but they are not necessarily the

same object.

Returning values vs attaching blobs

There are not strict rules when to return values and when to attach blobs. If the function by definition returns one obvious value (for example a computation of an average of a set), then returning a value is more natural. On the other hand, when a function is complex, produces various outputs than it is usully better to attach results as blobs. Also if a function returns more objects with nontrival sizes and potential consumers may read only part of inputs, it is better to use attaching blobs than returning a list of them.

Removing jobs

Generally removing a data while maintaining consistency may be a little bit tricky. Let us start with a demonstration where is the problem.

Why naive remove does not work?

Let us first show why naive removing does not work. Consider the following example with three builders, one for generating a random coin tosses, one is counting heads in the sample and one is counting tails in the sample.

@builder()

def sample_of_coin_tosses(sample_size):

return [random.randint(1, 2) for _ in range(sample_size)]

@builder()

def heads_count_in_sample(sample_size):

sample = sample_of_coin_tosses(sample_size)

yield

return [t.value for t in sample].count(1)

@builder()

def tails_count_in_sample(sample_size):

sample = sample_of_coin_tosses(sample_size)

yield

return [t.value for t in sample].count(2)

Let us assume that we do the following computations:

a = orco.compute(heads_count_in_sample(10))

b = orco.compute(tails_count_in_sample(10))

Obviously the a.value + b.value should be 10 (sample_of_coin_tosses(10)

is generated only once and reused in both computations)

But assume that we have a method naive_remove(job) that just removes stored

result job from the database. Let us consider the following scenario:

# ! this is only a demonstration of a problem, naive_remove is not implemented in ORCO !

naive_remove(sample_of_coin_tosses(10))

naive_remove(heads_count_in_sample(10))

After that only the result for number of tails remains. If we now call again the the code above:

a = orco.compute(heads_count_in_sample(10))

b = orco.compute(tails_count_in_sample(10))

The first line causes a computation and it induces also

to computing a new sample of coin tosses.

However, the second result is just loaded from the database as it already exists.

But a and b where computed on different samples!

So now you can get inconsistent results. For example, a.value + b.value does not hold.

This example is artificial, but this situation easily occur everywhere where you cannot reproduce you result exactly: in training neural network models, sampling a data sets, using some randomized heuristics, or simply just by library upgrade. When you cannot achieve the same result every time, naive remove does not work and causes inconsistencies.

Removing operation in ORCO

There are three types of removing jobs from database in ORCO: drop, archive, and free.

The simplest one is drop, it simply removes specified job from the database together with all jobs that recursively depends on the job. Removing dependant jobs prevents the inconsistency in the section above.

@builder()

def step1(x):

...

@builder()

def step2(x):

a = step1(x)

yield

...

# This computes step2(10) together with step1(10) as its dependancy

orco.compute(step2(10))

# This drops step1(10) and all its consumers,

# that is step2(10) in this case

orco.drop(step1(10))

Another option is archive, that sets a job and all its recursive

dependancies into state “arhived”. Such a job remains in database but it is

ignored by compute; builder’s function create a new job (in a normal

non-archived state). It also mean no new computation may depend on an archived

job result. Therefore the effect on computation is similar to drop, but you

can still reach archived data (e.g. in browser).

[Note that archive operation is reversible. Archived data may be put again back to active state, if it does not causes conflicts with the current active data. The restoring operation is not yet implemented. ]

# This computes step2(10) together with step1(10) as its dependancy

orco.compute(step2(10))

# This set to archived state step1(10) and all its dependants,

# that is step2(10) in this case

orco.archive(step1(10))

# Computes new step2(10), the archived job is ignored

orco.compute(step2(10))

Sometimes we want to free a data from the database but still use jobs that depends on this job for further computation. It is possible with free operation. Free removes all computed data by a job. However, to prevent the scenario from the section above, free operation leaves job metadata in the database and ORCO rejects any computation that would recompute the job. If you need recomputation of freed job, you have to archive or drop it.

# This computes step2(10) together with step1(10) as its dependancy

orco.compute(step2(10))

# Sets step1(10) into "freed" state and removes. Job step2(10) remains intact

orco.free(step1(10))

# This does not trigger a computation, it just load step2(10) from DB.

orco.compute(step2(10))

# This throws an error because the computation needs recomputing a freed object

orco.compute(step1(10))

Bulk removing

All methods have “_many” variant for dropping/archiving/freeing more jobs at once

orco.free_many([step1(20), step2(30)])

orco.archive_many([step1(30), step2(40)])

orco.drop_many([step1(50), step2(60)])

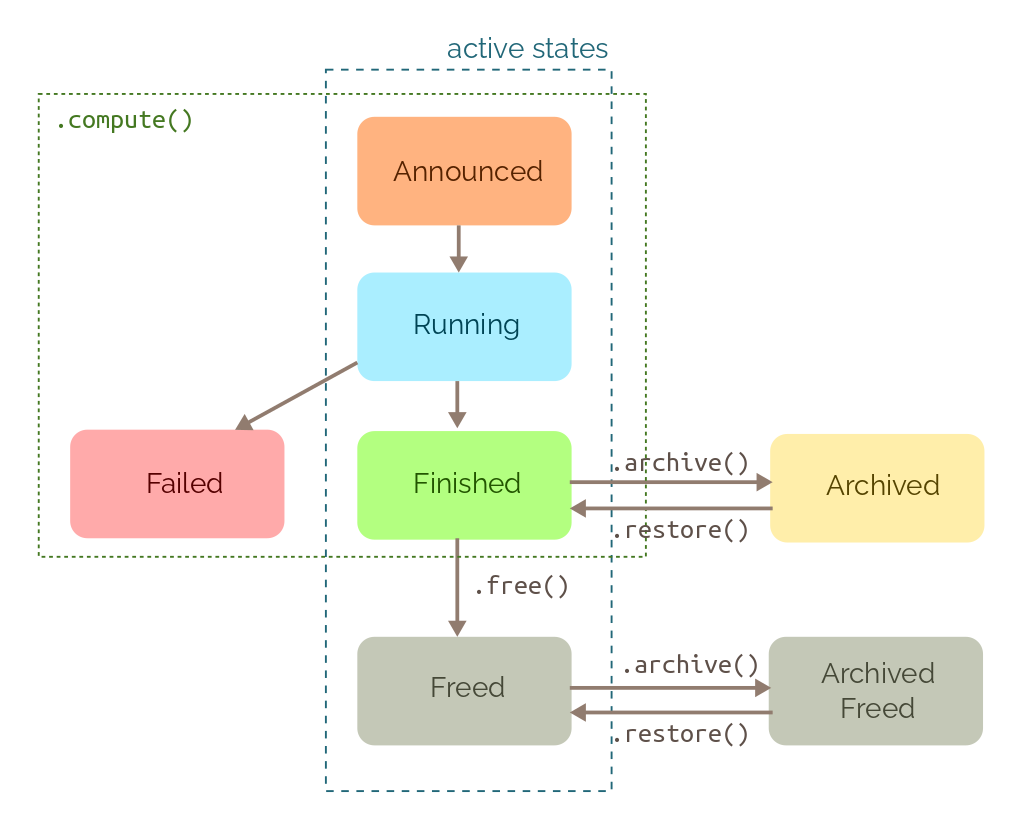

States of jobs

Each job is in one of the following state:

- Announced - The job was scheduled to computation.

- Running - The job is currently executed.

- Finished - Job is finished and its result are available

- Failed - An error occured during job’s computation

- Freed - Job’s data was freed by calling

orco.free()method. It cannot be used for computation any more while it also blocks recreaction of the task (details in section about freeing objects). - Archived/Achived free - Job was archived by calling

orco.archive(). It was removed from the set of active jobs. Its data are preserved but it cannot be used only for new computations.

For each builder and configuration, there is at most one job that is in active state (Announced, Running, Finished, Freed). This is invariant that helps to avoid recomputing already computed data, prevent simultanous computation of the same computation from different processes, and helps with consistency of results in case of data removal. And there may be unlimited number of jobs in non-active states.

Most methods like orco.compute() or orco.read() looks only for jobs in

active states and ignore others. There are two exceptions: If you want to get

all jobs under a given configuration, there is a method orco.read_jobs(),

e.g.:

@my_builder(x):

...

orco.read_jobs(my_builder(10))

The second exception is orco.drop(..) that removes jobs in all states.

Upgrading builders

Sometimes you have already computed some results, only to find out that you need to introduce a new parameter to your configurations. By default, this would invalidate the old results, because ORCO would observe a new configuration and it wouldn’t know that it should be equivalent with the already computed results.

For such situations, there is an upgrade_builder function which will allow you

to change the configurations of already computed results in the database

“in-place”. Using this function, you can change already computed configurations

without recomputing them again.

@orco.builder()

def my_builder(config):

...

# Introduce a "version" key to all computed configurations of a builder

def uprage_config(config):

config.setdefault("version", 1)

return config

orco.upgrade_builder(my_builder, upgrade_config)

Note that the upgrade is atomic, i.e. if an exception happens during the upgrade, the changes made so far will be rolled back and nothing will be upgraded.

Retrieving jobs without computation

If you want to query the database for already computed jobs, without starting

the computation for configurations that are not yet computed, you can use the

orco.read (or read method on a Runtime). If a job exists in the finished

stated, then it attaches job to the database entry. If there is not such job, an

exception is thrown.

The method orco.try_read works similarly, but return None is not in the database.

Frozen builders

When we want store a fixed collection of data that cannot be recreated, ORCO offsers frozen builders.

@builder(is_frozen=True)

def my_builder(x):

pass # Body is not important

Function of frozen builder is never called. We only utilize function’s parameters to define shape of configurations.

All results for the builder already in the database is available, but when a result is not presented in the database is requested, then error is thrown.

# Assume now an empty database

orco.compute(my_builder(10))

# Throws an error, because my_builder(10) is not in DB, and

# new value cannot be computed because my_builder is frozen.

New values can be inserted explicitly via insert function, which receives a configuration

and its result value:

# Insert two values

orco.insert(my_builder(10), 123)

orco.insert(my_builder(20), "xyz")

Note 1: Values can be inserted also for non-frozen builders, but usually you want to run

compute rather than insert for this case.

Note 2: A frozen state of a builder is a property of runtime, it is not stored in the database. Therefore

another process may normally create jobs into a builder that is frozen for other process.

Also for “unfreezing” a builder, just remove is_frozen=True flag and rerun the program.

Configuration equivalence

A configuration may be composed of dictionaries, lists, tuples, integers, floats, strings and booleans.

To check if a configuration has already been computed, it is serialized into a string key and queried

against the database.

In general, two configurations are equivalent if they are equivalent in Python (using the == operator),

with some exceptions:

- Lists and tuples are not distinguished, i.e.

[1,2,3]and(1, 2, 3)are considered equivalent. - Dictionary keys have to be strings, otherwise

{1: "a"}and{"1": "a"}would be considered equivalent. - Dictionary keys starting with an double underscore are ignored:

{"iterations": 100, "__note": "Foo!"}and{"iterations": 100}are equivalent.

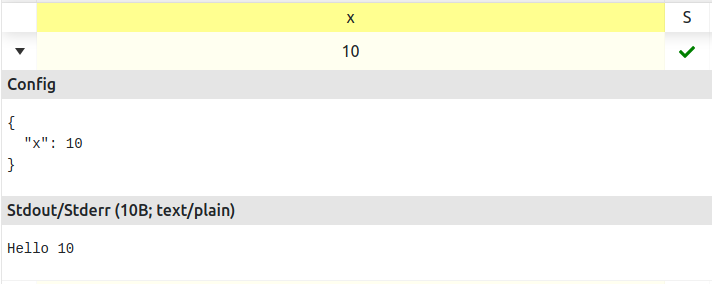

Capturing output

All standard output or error output is automatically captured and saved together as one of job attached data.

@builder()

def my_builder(x):

print("Hello", x)

orco.compute(my_builder(10))

The example above do not print any output when executed. It can be found in ORCO Browser:

Redirecting output to the terminal where the computation is runnig can be done

through JobSetup, that is described in the next section.

JobSetup

TODO

Configuration generators

ORCO comes with a simple configuration builder for situations when you want to build non-trivial matrices of parameter combinations (e.g. cartesian products with some “holes”). It enables you to build complex Python objects from a simple declarative description.

The builder is used via the build_config function. It expects a dictionary containing

JSON-like objects (numbers, strings, bools, lists, tuples and dictionaries are allowed). By default,

it will simply return the input dictionary:

from orco.cfggen import build_config

configurations = build_config({

"batch_size": 128,

"learning_rate": 0.1

})

# configurations == { "batch_size": 128, "learning_rate": 0.1 }

To build more complex combinations, the builder supports special operators

(similar to MongoDB operators).

An operator is a dictionary with a single key starting with $. The value of the

key contains parameters for the operator. The operator will return a Python object after it is

evaluated by the builder. The operators can be arbitrarily nested.

The following operators are supported:

$range: int | list[int]: Evaluates to a list of numbers, similarly to the built-inrangefunction.build_config({"$range": 3}) # evaluates to [0, 1, 2] build_config({"$range": [1, 7, 2]}) # evaluates to [1, 3, 5]$ref: str: Evaluates to the value of a top level key in the input dictionary. It is useful when you want to use a specific key multiple things, but you want to define it only once.build_config({ "graphs": ["a", "b", "c"], "bfs": { "algorithm": "bfs", "graphs": {"$ref": "graphs"} } }) """ evaluates to { "graphs": ["a", "b", "c"], "bfs": { "algorithm": "bfs", "graphs": ["a", "b", "c"] } } """$+: list[iterable]: Evaluates to a list with the concatenation of its input parameters (i.e. behaves likelist(itertools.chain.from_iterable(params))).

In this example you can see how it can be combined with a nested $ref operator.

build_config({

"small_graphs": ["a", "b"],

"large_graphs": ["c", "d"],

"graphs": {"$+": [{"$ref": "small_graphs"}, {"$ref": "large_graphs"}]}

})

"""

evaluates to {

"small_graphs": ["a", "b"],

"large_graphs": ["c", "d"],

"graphs": ["a", "b", "c", "d"]

}

$zip: list[iterable]:

Evaluates to a list of zipped values from the input parameters, i.e. behaves like list(zip(*params)).

build_config({

"a": {"$zip": [[1, 2], ["a", "b"]]}

})

"""

evaluates to {

"a": [(1, "a"), (2, "b")],

}

$product: dict[str, iterable] | list[iterable]:

Evaluates to a list containing a cartesian product of the input parameters.

If the input parameter is a list of iterables, it behaves like list(itertools.product(*params)):

build_config({

"$product": [[1, 2], ["a", "b"]]

})

# evaluates to [(1, "a"), (1, "b"), (2, "a"), (2, "b")]

If the input parameter is a dictionary, it will evaluate to a list of dictionaries with the same keys, with the values forming the cartesian product:

build_config({

"$product": {

"batch_size": [32, 64],

"learning_rate": [0.01, 0.1]

}

})

"""

evaluates to [

{"batch_size": 32, "learning_rate": 0.01},

{"batch_size": 32, "learning_rate": 0.1},

{"batch_size": 64, "learning_rate": 0.01},

{"batch_size": 64, "learning_rate": 0.1}

]

"""

When you nest other operators inside a $product, each element of the inner operator will be

evaluated as a single element of the outer product, like this:

build_config({

"$product": {

"a": {

"$product": {

"x": [3, 4],

"y": [5, 6]

}

},

"b": [1, 2]

}

})

"""

evaluates to [

{'a': {'x': 3, 'y': 5}, 'b': 1},

{'a': {'x': 3, 'y': 5}, 'b': 2},

{'a': {'x': 3, 'y': 6}, 'b': 1},

{'a': {'x': 3, 'y': 6}, 'b': 2},

{'a': {'x': 4, 'y': 5}, 'b': 1},

{'a': {'x': 4, 'y': 5}, 'b': 2},

{'a': {'x': 4, 'y': 6}, 'b': 1},

{'a': {'x': 4, 'y': 6}, 'b': 2}

]

"""

If you instead want to materialize the inner operator first and use its final value as a single element of the product, simply wrap the nested operator in a list:

build_config({

"$product": {

"a": [{

"$product": {

"x": [3, 4],

"y": [5, 6]

}

}],

"b": [1, 2]

}

})

"""

evaluates to [

{'a': [{'x': 3, 'y': 5}, {'x': 3, 'y': 6}, {'x': 4, 'y': 5}, {'x': 4, 'y': 6}], 'b': 1},

{'a': [{'x': 3, 'y': 5}, {'x': 3, 'y': 6}, {'x': 4, 'y': 5}, {'x': 4, 'y': 6}], 'b': 2}

]

"""

There is also a build_config_from_file function, which parses configurations from a path to a JSON file

containing the configuration description.

Continue to Best practices