orco.pages

Getting started

Example 1: Adder

In this example we will define a simple computation that adds two numbers. After you run the computation, its results will be stored in a database to avoid recomputation in the future.

The database with computation results is represented by a Runtime, which

receives a path to a database file where the results will be stored.

In this chapter, we use a default ‘job runner’ that executes task locally.

It is spawned automatically by the runtime, so no further action is needed.

As a database backend, you can use all databases supported by SqlAlchemy. For this text we will use SQLite, as it does not need any configuration.

In this chapter, we will also use one global Runtime, but ORCO is ready to having more non-global runtimes at once on one or more databases.

import orco

# Create a new global runtime

# If the database file does not exist, it will be created

orco.start_runtime("sqlite:///my.db")

# Use can use "sqlite:////" prefix for abolute path

# For using Postgress, you can use the following:

# orco.start_runtime("postgresql://<USERNAME>:<PASSWORD>@<HOSTNAME>/<DATABASE>")

Now we can start defining your computations. Computations in ORCO are defined as builders. A builder defines and stores the results of a single type of computation (preparing a dataset, training a neural network, benchmarking or compiling a program, …).

Let’s define a trivial builder that will returns of a computation which simply adds two numbers.

import orco

@orco.builder()

def add(a, b):

return a + b

orco.start_runtime("sqlite:///my.db")

# Note: It is ok to define builders before or after `start_runtime`

The builder is basically a wrapper around a function which result will be automatically persisted. Builder has some additional qualities that we will see later.

We call input arguments of a builder as a configuration of builder. Configuration has to be always composed only from to be JSON seriazable types (numbers, strings, booleans, lists, tuples or dictionaries). So it can be serialized with the result.

ORCO also always assumes that configuration fully describe the computation. This is important idea behind the concept of ORCO. It allows to prevent recomputing already computed data and reconstruct the computation when needed.

We have now defined a database for storing computation results,

a builder that defines a simple add computation

and two configurations for add that we want to compute.

To invoke a computation we need to create an job.

Job is created by calling a builder. Calling a builder is a very lightweight operation that just creates a reference

to a computation without invoking a builder’s function.

To really invoke a computation we need to call orco.compute(job).

After the computation is over, we can read job’s value.

# Compute the result of `add` with the input `config_1`

job = add(1, 2)

orco.compute(job)

print(job.value) # prints: 3

# Comment: orco.compute returns the first given argument, so the example

# can be written also as:

#

# job = orco.compute(adder(1, 2))

# print(job.value) # prints: 3

#

# We use both variants in this text.

Each builder establish a persistent cache for each builder that is stored in the database. Because this was the first time we asked for this specific computation, the build function was invoked with the given configuration and its return value was stored into the database. When we run the same computation again, the result will be provided directly from the database.

orco.compute(add(1, 2)) # Builder's function is not called now, it just load the result from DB

So far we have computed only one configuration, usually you want to compute many of them

jobs = orco.compute_many([add(1, 2),

add(2, 3),

add(4, 5)])

print([r.value for r in jobs]) # prints: [3, 5, 9]]

Computing more instances at once allows to paralelize the computation and reduce an overhead of starting a computation.

This concludes basic ORCO usage. You define a builder with a build function and ask the builder to give you results for your desired configurations.

The whole code example is listed here:

import orco

# Build function for our configurations

@orco.builder()

def add(a, b):

return a + b

# Create a runtime environment for ORCO.

# All data will be stored in file on provided path.

# If file does not exists, it is created

orco.start_runtime("sqlite:///my.db")

# Invoke computations, builder.ref(...) creates a "reference into a builder",

# basically a pair (builder, config)

# When reference is provided, compute returns instance of Entry that

# contains attribute 'value' with the result of build function.

job = orco.compute(add(1, 2))

print(job.value) # prints: 3

# Invoke more compututations at once

result = orco.compute_many([add(1, 2),

add(2, 3),

add(4, 5)])

print([r.value for r in result]) # prints: [3, 5, 9]

Example 2: Dependencies

ORCO allows you to define dependencies between computations. When a computation

A depends on a computation B, A will be executed only after B has been

completed and the result of B will be passed as an additional input to A.

In the example, assume that we have an expensive simulation. For the sake of

simplicity, we will parametrize it by one parameter p.

We define builder of simulations as follows:

import orco

import time

import random

@orco.builder()

def simulation(p):

# Fake a computation

result = random.randint(0, p)

time.sleep(1)

return result

Now we define an “experiment” that includes a range of simulations that has to be performed together with some post-processing.

Because we want share simulations between experiments, experiment itself will not perform the computation, but establish an dependency on “simulation” builder.

# Run experiment, sum resulting values as demonstration of a postprocessing

# of simulation

@orco.builder()

def experiment(start, end):

sims = [simulation(p) for p in range(start, end)]

yield

return sum([s.value for s in sims])

When dependencies are used, there are two phases:

- Inputs gathering (before

yield) - Computation (after

yeild)

We can call other builders in the first phase. They are gathered as dependencies for the computation. This phase should be quick without any heavy computation. This phase is possibly invoked more than once.

The second phase is computation phase where the main part of the computation should happen. ORCO guarantees that all jobs created in the first phase is successfully finished. Hence we may freely access its .value attribute. On the other hand, it is not allowed to create new jobs by calling builders (an exception is thrown in such case). All dependencies has to be created in the first phase.

Now if we run:

orco.start_runtime("sqlite:///my.db")

# Run experiment with with simulation between [0, 10).

orco.compute(experiment(0, 10))

The output will be as follows:

Scheduled jobs | # | Expected comp. time (per entry)

-----------------+-------+--------------------------------

experiment | 1 | N/A

simulation | 10 | N/A

-----------------+-------+--------------------------------

100%|██████████████████████████████████| 11/11 [00:03<00:00, 3.63it/s]

We see, that system performs one computation from builder “experiment” and ten from “simulation”. Simulations are automatically scheduled as a result of experiment dependency. Since our DB is empty, we have no prior information about computation time, the expected computation makespan is not available (third column in the output).

Lets us now run the following:

# Run experiment with with simulation between [7, 15).

orco.compute(experiment(7, 15))

The output will be following:

Scheduled jobs | # | Expected comp. time (per entry)

-----------------+-------+--------------------------------

experiment | 1 | 1ms +- 0ms

simulation | 5 | 1.0s +- 1ms

-----------------+-------+--------------------------------

100%|███████████████████████████████████| 6/6 [00:02<00:00, 2.95it/s]

ORCO schedules five simulations, because simulations for parameters 7, 8, and 9 are already computed. We need to only compute five simulations in range 10-14. Now we also see expected computation times for jobs because we already have some results in the DB.

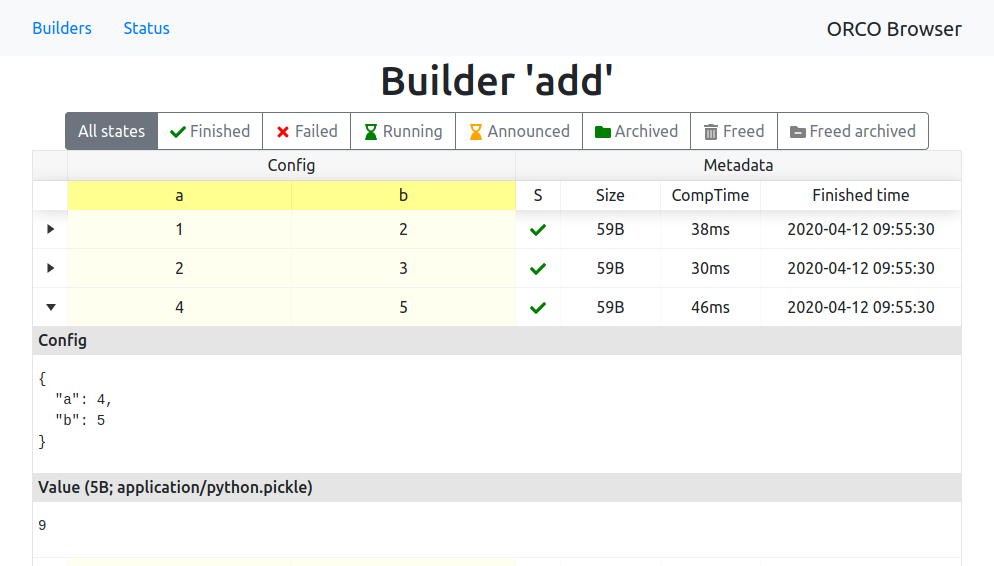

ORCO browser

ORCO contains a web browser of computations and their results stored in the database. It can be started by running:

orco.serve()

serve starts a local HTTP server (by default on port 8550) that allows inspecting

stored data in the database and observing jobs running in executors. It is completely safe to run computation(s) simultaneously with the server.

(The serve method is blocking. If you want to start the browser and run computations in the same script,

you can call serve(daemon=True) before calling compute on the Runtime.)

Continue to CLI interface